< back to Calendar >

25th Anniversary season

Music of Our Common Earth

Festival Concert 4

August 13, 2019

Tuesday

7:30 pm – Festival Concert at Darrows Barn

6:30 pm – Pre-concert lecture by Mark Mandarano

PROGRAM

Battistelli Orazi e Curiazi (1996)

Ayano Kataoka and Eduardo Leandro, percussion

Tan Dun Elegy: Snow in June (1991)

Wilhelmina Smith, cello; Tim Feeney, Ayano Kataoka,

Eduardo Leandro, Doug Perkins, percussion

--intermission--

Shostakovich Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok, Op. 127 (1967)

Hyunah Yu, soprano; Jennifer Frautschi, violin; Wilhelmina Smith, cello;

Ignat Solzhenitsyn, piano

Artists

Hyunah Yu, soprano

Jennifer Frautschi, violin

Wilhelmina Smith, cello

Ignat Solzhenitsyn, piano

Tim Feeney, Ayano Kataoka,

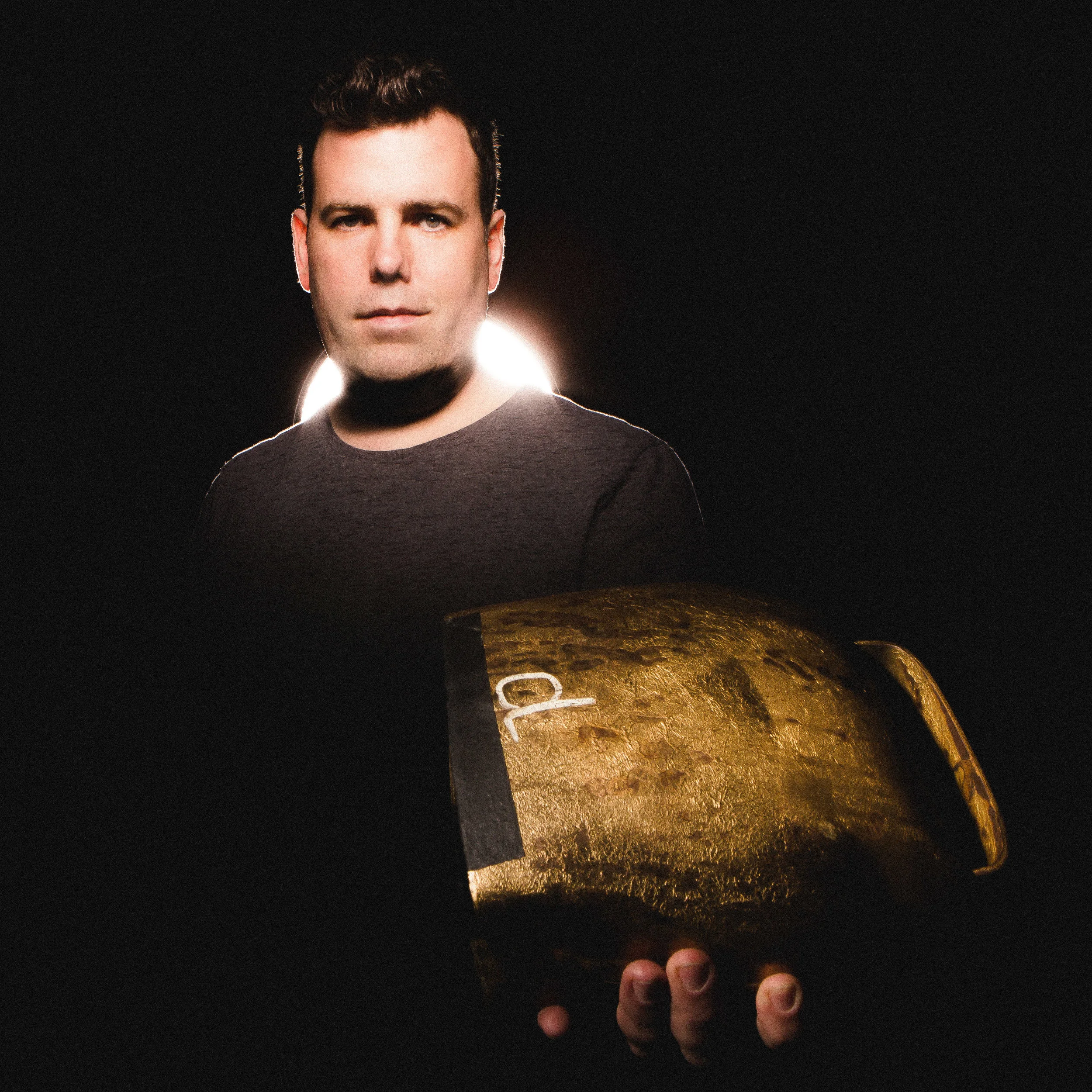

Eduardo Leandro, Doug Perkins, percussion

Program Notes

Music can give powerful expressive voice to the idea of an individual caught up in historical events beyond their control, as in many operas where the settings among battles, revolutions, and coups d’etat lend love triangles and efforts toward justice an urgency and grandeur they otherwise might not have. In chamber music, the cultural-historical setting of works can be achieved through text and sound to bestow a broader meaning. Snow in June, by Chinese composer Tan Dun, turns to a historical legend of injustice in which a young woman becomes as a martyr through a perverse miscarriage of justice. The music of Battistelli’s Orazi e Curiazi calls on the performers to re-enact the roles of willing combatants upholding honor. In Shostakovich’s setting of poems by Alexander Blok, the words seem to portray the circumstances of common people buffeted by events as well as the artists who use their gifts to speak for the masses.

In its earliest days, when Rome was little more than a village among many on the Italian peninsula, a dispute arose between the Romans and the kingdom immediately to the south, Alba Longa (in the Alban Hills where Frascati and Castel Gandolfo lie today). The two sides managed to agree that a bloody battle would devastate the armies and the populace of both peoples and leave them vulnerable to subsequent defeat by the Etruscans to the north. Instead it was proposed that each party select champions who would combat each other and that the victors in this contest would determine the result. One family on each side was given the honor of representing their people: on the Roman side, the sons of Horace, the Horatii (Orazi in Italian); and on the Alban side, the sons of Curiatius, the Curiatii (Curiazi). The willingness of these representatives to sacrifice their lives in order to spare the lives of their countryfolk has long been seen as symbol of honor and duty.

Battistelli describes his piece as follows:

My score develops on the idea of a narration, with concrete and metaphysical sounds, of one of the most fascinating myths in the history of ancient Rome. It is the duel where the body and the voice of the two performers, the timbre and the rhythm of the percussions become elements of a fantastic dramaturgy.

The percussionists take on the role of combatants as they expostulate, laugh, or cry out in threatening tones. They stamp and rustle their feet in gravel. They eye each other with menace. Chamber music is often considered one of the highest forms of conversation; in this work, it is not simply an argument, but a contest and a battle.

The central image of Snow in June comes from the 13th-century Chinese drama by Kuan Han-Ching in which a young woman, Dou Eh, is executed for crimes she did not commit. Before her judges, she says, “Those who are kind are poor and die young, while evil-doers enjoy wealth and longevity. Heaven and earth both bully the weak and fear the strong, not daring to go against the flow.” Nature cries out at this injustice: her blood does not fall to earth but flies upward, a heavy snow falls in June, and a drought descends for three years. Tan Dun’s Elegy: Snow in June sings of pity and purity, beauty and darkness, and is a lament for victims everywhere. Although this is called an “elegy,” it does not have the reflective, consoling effect one might expect. Rather it is urgent and filled with conflict.

Alexander Blok (1880–1921) was a poet of prophetic, ominous, doom-laden verses. In his poetic world, the images of the present hold futurity within them and are presented as symbols, not explained concretely. At first, Blok was a great believer in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and saw within the conflagration the possibility for a new future. Blok’s cultural importance was such that one of the leaders of the Revolution, Leon Trotsky, penned a lengthy assessment of Blok’s relevance to Revolutionary principles: “Blok, the ‘purest’ of lyricists, did not speak of pure art, and did not place poetry above life. On the contrary, he recognized the fact that ‘art, life and politics were indivisible and inseparable.’” Ten years later, however, Blok was disillusioned with the aftermath of the Revolution, suspected of conspiracy, and became another casualty of the Bolshevik oppression.

In 1967, to say that Shostakovich was disillusioned would be quite an understatement. Politics aside, he had suffered a heart attack, after which he felt that he had lost the impulse to create—something he associated with being denied access to cigarettes and alcohol. One is not certain how seriously to take this claim but, in a letter to a friend, he wrote that one day while his wife was out of the house, he opened a drawer and found a partially filled bottle of brandy that somehow had been overlooked and, after a short time communing with this muse, he found the will to compose once again!

The impetus for the Seven Romances on Poems by Alexander Blok came from his colleague and friend, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who requested from Shostakovich a duet that he could perform with his wife, soprano Galina Vishnevskaya. Shostakovich quickly set the lyrics to the poem by Alexander Blok that takes the point of view of Ophelia who pines after the distant Hamlet. However, now that the composer’s inner creative engine had reignited, it seemed to take on a will of its own and Shostakovich composed one song after another, beginning with more duets, for soprano and violin, then soprano and piano, then intermingling these combinations until all four musicians came together in the final song. Blok’s lyrics certainly lend themselves to musical settings—as he noted in his own words, “I am accustomed to assemble the facts accessible to my eye in a given time in every field of life, until I am sure that in combination they create one musical chord.”

The music is spare and spacious, allowing the text and vocal line to remain prominent. The text setting follows in the footsteps established for the Russian language by Mussorgsky: syllabic, often repeating a single pitch or moving within a narrow range, allowing for melismatic ornaments only in special places. In “The Storm,” we see a metaphor for revolution and turmoil. “O, how wildly outside my window/The savage tempest roars and rages/The scudding storm clouds unleash the rain/And the wind howls as it fades!” In “Secret Symbols,” we can sense through vague visions the struggles that portend: “The canopy of the sky hangs low above me/A dark dream lies oppressive in my heart./My predestined end is near/War and flames lie ahead...” And in “Gamayun,” the prophetic bird, we see an affirmation of the poet (and composer) as the voice of warning, predicting a dire future: “Seized by primоrdial terror/Her beautiful face burns with love/But with prophetic truth resound/Those lips stained with blood!”

By Mark Mandarano